Introduction

Nand2Tetris is a hands-on computer science course, guiding learners to create a basic computer which is capable of running programs written in a high level programming language – from the ground up.

The course starts with the single logic gate “NAND”, and through the first half of the course, a computer is built which is simulated in the course’s emulators. In the second half of the course, code is written to create a compiler for this computer, which converts a high level programming language to instructions the computer can operate on.

Notably, the course is freely available online. Addionally, the course follows the book “The Elements of Computing Systems: Building a Modern Computer from First Principles” by Noam Nisan and Shimon Schocken, which was an helpful resource along side the online forum.

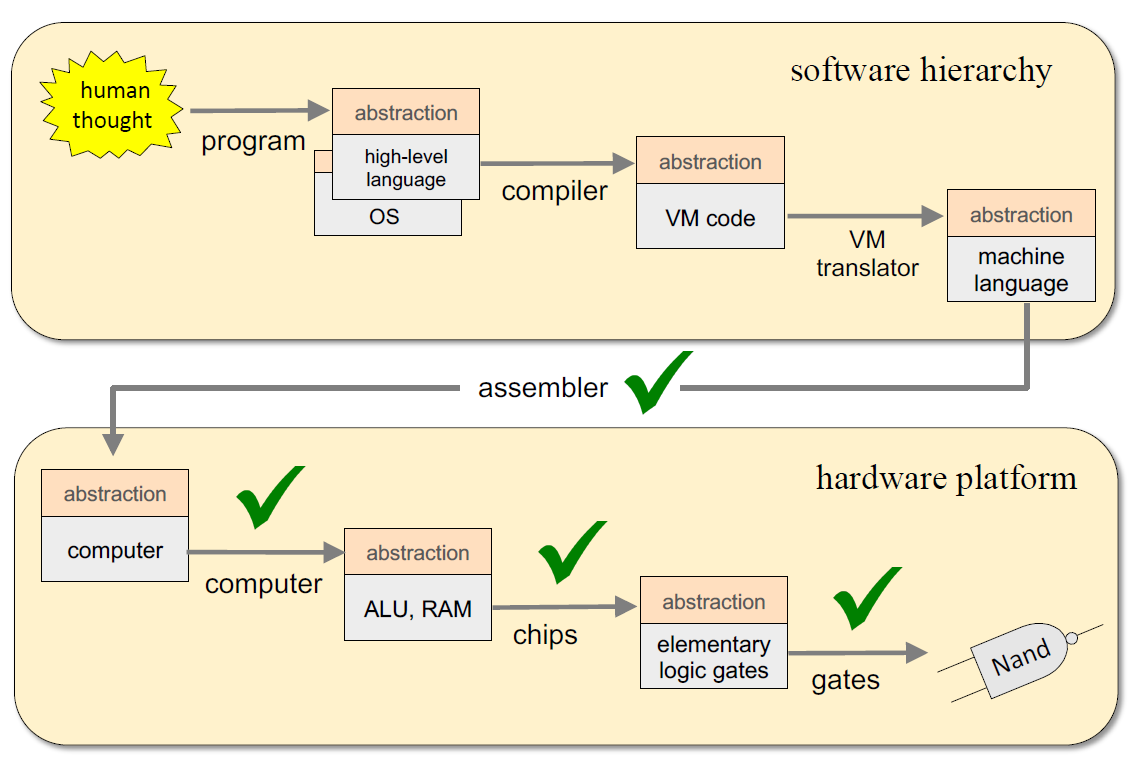

Each chapter builds progressively on the previous one, covering topics such as Boolean logic, hardware description languages, computer architecture, machine language, assembly programming, compilers, and even operating system fundamentals. The figure below shows how these elements come together to translate human thought into on/off states of a series of NAND logic gates.

By the end of the course, a simple, yet capable 16 bit computer is created which can run an object oriented programming language. Compilers are written to translate between the high level programming language, virtual machine code, and assembly code. Finally, operating system functionality is added. The course leaves it to the student to continue work such as:

- Programming a game (such as Tetris)

- Extensions to the computer architecture and programming languages

- Performance optimizations

Below, I briefly describe the course scope. Afterwards, I detail my choice of extending the course by creation of a Tetris-like game. And finally, I add some commentary and reflections looking back at the course.

Course Scope

The course covers the following topics (click to expand):

Hardware:

Boolean arithmetic, combinational logic, sequential logic, design and implementation of logic gates, multiplexers, flip-flops, registers, RAM units, counters, Hardware Description Language (HDL), chip simulation, verification and testing.

Architecture:

ALU/CPU design and implementation, clocks and cycles, addressing modes, fetch and execute logic, instruction set, memory-mapped input/output.

Low-level languages:

Design and implementation of a simple machine language (binary and symbolic), instruction sets, assembly programming, assemblers.

Virtual machines:

Stack-based automation, stack arithmetic, function call and return, handling recursion, design and implementation of a simple VM language.

High-level languages:

Design and implementation of a simple object-based, Java-like language: abstract data types, classes, constructors, methods, scoping rules, syntax and semantics, references.

Compilers:

Lexical analysis, parsing, symbol tables, code generation, implementation of arrays and objects, two-tier compilation.

Programming:

Implementation of an assembler, virtual machine, and compiler, following supplied APIs. Can be done in any programming language.

Operating systems:

Design and implementation of memory management, math library, input/output drivers, string processing, textual output, graphical output, high-level language support.

Data structures and algorithms:

Stacks, hash tables, lists, trees, arithmetic algorithms, geometric algorithms, running time considerations.

Software engineering:

Modular design, the interface/implementation paradigm, API design and documentation, unit testing, proactive test planning, quality assurance, programming at the large.

Capstone Project: Tetris

Programming a game like Tetris was much more involved that I thought – but like the rest of the course, I broke it down into smaller, more manageable parts that can be developed and tested. The following details the development of the game, in the order it occurred.

At first, two classes were created. One that represents a tetrimino (the game pieces that each contain four blocks), and a second that represents the game itself.

This tetrimino class draws sprites (a fixed bitmap image) to show where the four blocks are. It can also hide those sprites by drawing them in white, which is necessary before movement can occur otherwise it would ghost across the screen. Translation and rotation inputs are handled from the user as key presses. Rotation is achieved by keeping track of the rotation increment, and performing a lookup to get the relative location the blocks should be drawn at. At this stage, only the “T” tetrimino can be produced.

The game class listens for key presses, and handles tetrimino creation and disposal. More game functionality is added later.

Next up was to add collision detection between other tetriminos and the walls of the game. The tetrimino class does this by simply looking at pixel values. When a bottom collision is detected, that tetrimino object is disposed of, leaving its “ghost” blocks in place. A new tetrimino is then created at the top of the game.

The game class watches for complete lines and clears them recursively at each time step of the game. If a complete line is detected, it clears that line, moves all the existing blocks downward, and re-checks for complete lines.

The rest of the tetrimino shapes were then added. To chose the next shape, a pseudo-random number generator was created using the Linear Congruential Method, which uses simple operators (plus, multiply, and modulo) to generate a sequence of seemly random numbers based on an initial seed. At this point, the seed was hardcoded, so the game would still generate the same order of shapes every time, but we will see this improved later. A indicator for the next shape was also added.

An interesting addition to the complexity I didn’t think about initially is that in certain cases tetriminos need to be moved off the wall if they are rotated. Otherwise, their shape would overlap the wall or other tetriminos. To solve this, the code temporarily allows the rotation first and checks for overlap (since the blocks are hidden before movement, the user never sees this). If overlap is present, a move away is attempted. If the move is successful, the rotation is allowed. Otherwise, the rotation is undone.

After the following changes, the game started to become fun to play during testing! The tetriminos now move down automatically, at an increasing speed determined by the current level. Scores are calculated based on the number of lines cleared at once as well as the current level. A game over is detected if the tetriminos pile up too high.

Also, the game is no longer deterministic in the way that tetriminos are chosen – the pseudo-random number generator is seeded by the time (technically… number of computer cycles) from initial start up to the first key press.

Finally, the user can hold the down arrow to rapidly send the tetrimino downward. This last addition required re-writing the key detection code completely. The clock cycles elapsed was recorded and certain game functions only occur based on a delay. Rather than the code waiting for the next key press, it continuously checks for new key presses. Programming smooth game operation on such a simple computer and language was an interesting challenge as I was used to more advanced constructs like hardware interrupts to check for hardware pin states.

Finally, after a bit of visual clean up and a “Press Start” type game entry, I’m pleased to present the final version of the game:

Comments & Reflections

The Journey

This was by far the biggest undertaking in self-learning I’ve taken on. It’s tough to know the total hours put in, but I’d estimate roughly 20-30 hours on each of the 12 chapters, plus the Tetris game creation.

This course was an incredible journey that fulfilled my desire to understand things from first principles. Many of the topics I had heard of but were always “black box” mysteries.

“Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” -Arthur C. Clarke

The course explains these black boxes systematically, and building them yourself allows you to truly internalize and understand them. But after at each step, it’s necessary to turn them back to into black boxes, i.e., abstracting them away so you can focus on the next level of complexity. This allows you to fully grasp these constructs’ rationale and realize their capability by using them without having to worry about their low level details.

The Beauty

Over completing this course, it was amazing to see what seemed like arbitrary design decisions materialize into meaningful simplifications, optimizations, or elegant solutions to complex problems.

- One of the design decisions is to break apart of the high level compiler two stages – high level to virtual machine code, and virtual machine code to assembly code. The stack architecture that the virtual machine implements conveniently solves the implementation of abstract ideas like a function, and what it means to return from a function and recursively call a functions.

- Some of the optimizations are seen in the Math library that is creating using the high level language. Since the computer’s ALU (Arithmetic Logic Unit) can only handle simple operations like add, subtract, bitwise ‘and’, ‘or’, and ‘not’, functions like multiply and divide must be created higher up in the architecture. Elegant numerical methods are used to solve multiply, divide, and square root are implemented whose performance (number of low level operations) scale with bit count rather than digit count.

I can also commend the authors successful efforts to create a architecture that is simple enough for one person to learn in a reasonable amount of time, yet powerful enough to be capable of running fully functional, interactive programs. Along the way, they are careful note where complexity has been left out intentionally to leave the course a reasonable length – and where further learning can be had.

Lessons Learned

- To implement the assembler (converts virtual machine code to assembly code) and the compiler (converts high level code to assembly code), I used Python as I enjoy using the language and was hoping to become more proficient. In completing this course, I feel I’ve not only become a better Python programmer, but a better programmer in general.

I had previously hesitated to implement classes, (relying mostly on code abstraction by functions). I learned how useful even a simple class can be for creating legible, simple code. - This project was sufficiently complex that I truly learned the value of unit testing individual functions and classes – and leaving those tests intact to come back to and expand upon. Whenever I had doubt about what was happening with my code, I could create more intricate or specific tests of my previously written code to verify what I was relying on was working correctly.

In particular, using this bit of Python code:

“if name == ‘main’:” was useful in running test code on classes and functions, without having the test code run when calls to those classes and functions were made. This is a convenient way to keep the test code intact.