Introduction & Motivation

This project is a less expensive alternative to a professional bike trainer (i.e., like one used in gyms) that records your workout with statistics like speed, power and energy output. It was also my first experience learning how to program Arduino microcontrollers.

The trainer is a fixture that the rear axle of a bike mounts to, providing resistance to pedal against. In this project, a custom built encoder is added to the trainer to speed measurement, an Arduino reads the encoder and transmits the data over a serial port to a PC. This PC reads the data using MatLab, calculates power, and plots the live data.

Hardware

The trainer is a Kinetic Road Machine, which has a power vs. speed curve is available from the manufacturer (at time this was not common). The trainer includes a large flywheel to make the experience feel more like riding on the road. The flywheel provides an easy surface to affix an encoder to measure speed.

To create the encoder, half of the flywheel is coated in Pasti-Dip to create a black, matte surface. This contrasts to the reflective machined steel surface of flywheel. A QRD1114 is mounted in close proximity to the flywheel, which is a IR LED and a IR photo-transistor combined in a convenient package.

An insulated tin box houses a small solderable prototyping PCB. An Arduino Teensy 3.1, pull-up resistor and leads from the QRD1114 are soldered to the PCB and a USB cable provides the data connection as well as 5V power.

Software

Teensy

The Teensy runs a sketch that uses an interrupt pin to obtain a count of encoder pulse. Using the time elapsed, the flywheel speed is calculated and speed and time data is transmitted over the serial port. To make sure the input buffer is not overrun, the Teensy waits for a ready signal from the PC.

PC Host

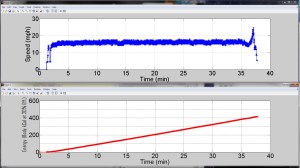

A PC runs a MatLab script that sends “ready” control bits to the Teensy serial port and reads the time and flywheel speed data. Bike wheel speed is the determined from encoder speed data and the ratio of the roller and bike wheel diameters. Power is determined from the speed-power curve of the trainer, and bike speed and energy output are live plotted on screen.

Comments & Lessons Learned

- Originally, this project was prototyped by measuring the time between digital state changes on the encoder signal. The Arduino delays in timing to acquire a reasonable amount of data, and some quantization error results from not exactly capturing the rising and falling edges of the pulse. I eventually learned to use interrupts, which is a more elegant solution for measuring encoder pulses. In this mode, the main program loop pauses and counts pulses on the digital input pin for a short time.

- The coding to get the Teensy and MatLab to communicate actually took the most time to get working out of this entire project.

- Sending ASCII formatted characters is certainly easier to get working since it’s easier to troubleshoot using the Arduino Serial Monitor. Data transmission occurs fast enough to update the live plots, otherwise, I would go to binary over ASCII.

- The handshake from MatLab to the Teensy does take execution time, but is well worth it to know exactly how these two are interacting.

- This site had some information that was extremely useful in getting MatLab to send control bits in the correct format. I had been trying to get this to work with ANSI formatting, but it would only work sending characters, not numbers. In trying to send a ‘1’, fprintf(s,’%c/n’,’a’) would work, but fprintf(s,’%d/n’,1) would not. fprintf(s,1) will be read correctly by the Arduino with Serial.read().

- To convert raw power and energy to human output values is iffy at best. I found a couple sources that state around 20-25% efficiency. I use 20%, which gives me an estimate of Calories burned. But as far as a trainer, all I really care about is relative performance, so it really doesn’t matter if I convert to human Calories. Source 1. Source 2.

- I learned to get clean lines with Plasti-Dip, spray a heavy coat and quickly remove your masking. If you wait until it starts to tack, the mask will tear off extra material.

Parts Listing

- Kinetic by Kurt – $379.00

- Optical Detector / Phototransistor – QRD1114 – $0.95

- Resistor Kit – 1/4W (500 total) – $7.95

- Hookup Wire Kit – $20.00

- Adafruit Perma-Proto Small Mint Tin Size Breadboard PCB – $7.95

- Teensy 3.1 + header – $19.95

- Hose Clamps, Bike Inner Tube, Aluminum Rod, Zip Ties, Altoids Tin, Liquid Electrical Tape

Total: Roughly $450, with plenty of spare resistors, hookup wire, and 2 PCB’s for other projects.